We are talking about Sara Giller and the climbing accident that almost killed her. We hope that you find her words and advice as inspiring as we did.

I feel stupid. I feel stupid in a way that I can’t recover from. I was an English major at Columbia University, I got A’s – not always, but there were a few – and now it’s difficult for me to even write my thoughts down. It wasn’t always that way.

Sara Gillers, with part of her skull missing after a cinder block-sized rock fell on her while belaying.

In a world where people wear helmets for so many sports, why do the majority of sports climbers climb without a helmet? Perhaps more importantly, why do sport climbers refuse to wear helmets and sometimes chastise those who do? Today, not many people bike, ski or snowboard without a helmet. Times have changed from where they were just ten years ago. But why do sports climbers still climb without one?

(Also, check out another interview with Shauna Coxsey, here!)

Helmet That Can Say You From Climbing Accidents “Advice”

I did not always climb with a helmet, and my life changed forever when a large block of rock fell on my head. The resulting traumatic brain injury almost killed me. Even though it happened six and a half years ago, I deal with the effects of that accident every day. Accidents happen. And what happened to me does not have to happen to you. I am sharing my experience to remind climbers how important that silly-looking “brain bucket” is.

I have spoken about the facts of the accident multiple times, but right now I want to talk about how I still feel the effects of a decision I made when I was 26. A decision that is still hurting me at 32 and that I will be feeling the effects of for the rest of my life.

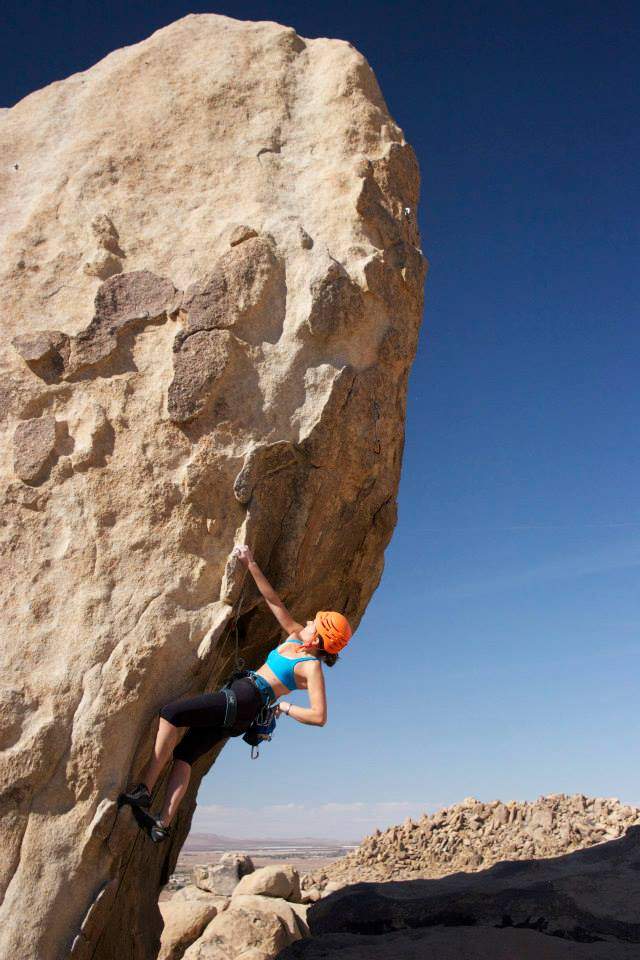

Sara climbing 3 years post-accident in Bishop, CA. Photo credit: PARockJock

When I heard the story of what my rescue was like; what it was like for the days I was in a coma; how excited people got when I wiggled my toes; I thought, ‘wow, that person was fucked up. What happened to her? Did she ever wake up?’ It’s hard to realize that that girl was, in fact, me. I survived, but I still can’t grasp how bad it was. It does not feel like I almost died.

There are ways in which I protect myself. I keep my feelings about the severity of my accident at an emotional distance because I do not want to feel like I am the victim of the accident, but that I have moved on and healed. I am scared to accept how close I was to death. Now whenever I hear about people not wearing helmets or adults taking children climbing without wearing helmets, I get upset.

When climbing teams take the next generation of climbers outside without wearing helmets, and teach these unsafe habits, I get upset. I am sharing my experience because I wish someone had warned me about what could happen if I didn’t wear a helmet. I wish I were not consumed with the vanity of not looking “cool” while climbing with a helmet six and a half years ago.

Because now, when I look at my face in the mirror, I see the results of an accident when I didn’t wear one. I see the huge dent in my head where the temporalis muscle atrophied, that even reconstructive surgery could not fix, and sometimes I get nostalgic, wishing my head were still fully shaped. I also see the huge scar that goes from my forehead to the back of my head where hair won’t ever grow again and when my hair is wet, is visible and looks a little frightening.

The fact that often little kids look at the tracheotomy scar on my neck, point to it, and ask, “What’s that thing on your neck? It looks like you were stabbed there.” So I explain that I couldn’t breathe so the doctors needed to put a hole in my throat so that I could. I am not writing this article so that people feel bad for me, I am writing this article so that the climbing world can hear the story of how bad it can be.

It was not a user error or equipment failure. It was a fluke accident when the rock fell. It was a lack of equipment that was my error. I should have been wearing a helmet.

Sara climbing Fall Line at New River Gorge, pre-accident. Photo credit: DPM

The Time When A Block Fell On My Head

On January 12, 2008, I was climbing with friends at East Peak in Meriden, CT. I was belaying my friend who was climbing Cat Crack. When he was about 50 feet up, he accidentally dislodged a cinder block-sized rock that fell 50 feet, landed on the back of my head, fractured my clivus (part of the skull that protects the brain), and knocked me unconscious immediately. Because I was using a Gri-Gri, my climber was caught, and in turn, his weight kept my limp body from falling off the belay ledge. It was dumb luck that I was using a Gri-Gri that day and that piece of gear kept us both alive.

Condition Was Terrific When Got Rescued

My friends lowered my limp body and after a two-hour evacuation, with a rescue crew of 18 firefighters (see photo below), I was taken by a helicopter to St. Francis hospital in West Hartford, CT. There the brain surgeries began in an effort to save my life. When I entered the hospital, I was in a coma. I was a three on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), which essentially means that I was almost dead. Because of this, the neurosurgeon did not want to do an invasive craniectomy, a surgery where a part of the skull is removed to allow the brain to swell without causing further brain damage.

The surgeon was not convinced I was going to survive, so he felt the surgery was unnecessary. Luckily, my parents, five siblings, and the chief of neurology at Brighman and Women’s Hospital (BWH) advocated for me and convinced the neurosurgeon to do the necessary craniectomy so that no more damage was done to my brain. Two days at St. Francis and a few brain surgeries later, I was flown to BWH, where I had more brain surgery and spent the duration of my coma in the Neuro ICU.

Bouldering at Bishop, post-accident.

While I was in the coma, the BWH neuro team had a meeting with my parents and siblings to warn them of the possible outcomes: that I might wake up in a few months a completely different person. When the doctors didn’t say anything else, Chanani, my brother who drove in from New York, asked, “You said there was another possibility, what is it?” The doctor responded, “She might not wake up at all.” Death was a realistic possibility for me.

Of course, I have been told all of this. It’s a story of what happened to a girl who was in a climbing accident and ended up in a coma. I can’t imagine what I looked like in the hospital with fifteen tubes coming out of my body in every direction, attached to multiple machines to monitor my breathing and brain activity. My mother tells me that she sat by my bed and just prayed for days on end. My parents, who are both full time physicians, took off from work and sat with me in the hospital so that they could monitor my every move, hoping that I would move more than the occasional involuntary movement.

My youngest brother Yosef, who flew in from Israel the night of my accident, sat with my parents and prayed with them, holding a vigil over my hospital bed.

After a ten-day coma, I beat the odds; surprised my family and the doctors, and woke up.

Sara with the Meriden rescue crew that transported her after the accident.

Accident Changed My Life 360

When I was ready to leave the neuro ICU, I was discharged to Spaulding Rehabilitation Center where I relearned how to walk and talk and be a functioning person. When I first got there, I didn’t understand why I was there. I was confused. People kept telling me that I had a brain injury, but it didn’t mean anything to me. I was on a lot of sedatives and painkillers when I first got there.

I was on so many drugs; I thought that I could remove my head from the rest of my body so that I didn’t have to wear a helmet when I got up. Though, in reality, I did need to wear a helmet whenever I walked around because a third of my skull was still not in my head due to the craniectomy. I don’t remember learning how to walk or talk again.

I think I knew that something happened and my life was changed forever, but I did not understand what, even though everyone kept on telling me “Sara, you were in a climbing accident, you have had a brain injury, you are in Spaulding Rehab.” It was a broken record to me until I realized what happened. That realization happened two weeks into my stay at Spaulding, when I found out I couldn’t climb for a long time. Climbing had been my life, if I couldn’t climb, what would my life be like?

After I heard that I read through all the updates that my parents had posted on a website, and I slowly began to realize how bad it was.

This accident is something that has profoundly changed my life. It has affected me in ways that I am still learning about today. I can’t remember the ten days that I was in a coma or the week after I woke up. I didn’t understand why everyone was so excited about me smiling or wouldn’t let me go to the bathroom without someone watching me. I didn’t understand and I still don’t really know what happened to me in those days. I have accepted it as time I will never get back, yet it has dramatically changed the course of my life forever.

A few days before I left Spaulding, I started to realize that once I left the hospital, I would be in the real world where not everyone was wearing helmets all the time because not everyone had some sort of brain injury. Benyomin, my brother who flew in from Toronto, came into my room and asked if I was excited about going home. I said, “Yes”. And then I said, “No, I am scared”. I was scared about the real world. I’d been in hospital for the past six weeks and I was scared to face the reality of my accident; that my life would be different and would never be the same again.

How I Stayed Strong To Start Over Again

I started to cry for the first time since I got hit. I was crying because I was scared. I didn’t know how I was going to deal with the reality of having this horrible accident happen. After this, I didn’t cry for another four years. I didn’t want to feel vulnerable and weak, like a victim so I disconnected myself from my emotions.

Sara, climbing in Verdon, France, post accident.

Two weeks after I left Spaulding, I had surgery to put my skull back. It was originally stored in my abdomen to keep the tissue alive while the swelling in my brain subsided, but once I got to BWH, it was removed from my abdomen, and stored in a cryogenic freezer. I was going to be whole again! This was the first brain surgery that I could remember because all the other ones happened when I was in a coma; it felt weird prepping for surgery.

Because I had had so many IVs over the past two months, the nurses had a hard time finding my veins; it was like my veins ran away from the needles. The nurse needed to use a pediatric needle, the smallest they could find, to start the IV. I remember waking up from the surgery and being so thirsty, but they wouldn’t give me any water. I kept asking for a drink, but they were scared I was going to throw up, so they only gave me ice chips.

Once I got the ok to drink something, I asked for some ginger ale with a splash of cranberry juice, a favorite Spaulding beverage. I remember the nurse mocking me, saying, “What do you think I am, a bartender?!” During this surgery something happened to my olfactory nerve, and as a result, I could not taste or smell much for the next four years. My parents started going back to work, but I still was not allowed to be home alone. I was a 26-year-old woman who needed a babysitter.

Nothing’s going to stop this woman! Tyrolean traverse in Verdon, post accident.

After Spaulding, I spent two more months in rehab at Community Rehab Care (CRC), an outpatient facility, where I received speech, occupational and physical therapy. Upon my “graduation” from CRC, I gave a lecture on Hamlet in speech therapy and got to go to the climbing gym with my physical therapists. I was back at work in my lab as a research assistant by the end of May and climbing inside again, I no longer needed a baby-sitter and I could finally start driving again. Six months after my accident, I felt like I was getting my life back.

But in November 2008, I needed more brain surgery to drain a subdural hematoma and do a reconstruction of the temporalis muscle that atrophied while my skull was not in my head. Four days after this surgery I had a seizure; and as a result, I could not drive and had to stop climbing for another six months. This was a serious setback for me; it felt like my recovery was starting from scratch. The seizure caused so much damage to my brain that I could feel the effects. My memory got worse, I couldn’t stay focused long enough to read a chapter in a book.

I would watch TV shows, knowing that I had already seen the episode, but since I completely forgot what happened, I would watch it again. I went to a friend’s holiday party, and a climber, who I recognized came up to me and said, “It is so good to see you here. You are so lucky.” I wanted to punch him in the face and say, ‘No, you are so lucky. You can drive. You can climb- inside and out. You can ski. I can’t do any of that.’

Or other people would come up to me and say, “God must really love you. God saved you.” And my response to those people was, “Well, if a god saved me, then a god also threw a rock on my head and put me in a coma.” I know that all those people meant well, and what they really meant to say was, ‘Sara, considering how bad things were, you are lucky that you survived.’ But hearing people tell me I was lucky just made me angry. I didn’t feel lucky. Those six months were the darkest and hardest I can remember from my recovery.

Sara on Steve’s Arete (AZ) during her cross-country trip after deciding to return to outdoor climbing.

Accident Caused Not Only The Head Injury

When the rock fell and fractured my skull, it also fractured a bone in the middle ear, which caused a significant hearing loss on my left side. As that fractured bone healed, a cholesteatoma (noncancerous tumor) developed in that ear. In February 2010 I had surgery to remove the growth, which turned out to be three that had grown in different places of my left ear. Over the next year and a half, I was still having ear problems, so I had more surgery on my ear in November 2011. It is now May 2014, my ear is still not perfect, but I have been surgery-free since November 2011!

Throughout my entire recovery, I kept thinking that once my doctor said I could climb outside, life would be like it was before my accident. I was wrong. In March 2010 I had an appointment with my neurosurgeon. I thought I was going to get her blessing to climb outside again, but I learned that my skull never fused when she put it back two years earlier; there is a divot along with my head scar where the skull is misaligned. It will probably never fuse, if you ever see me, ask to touch my head, it’s a very tangible misalignment. As a result, I am at serious risk for paralysis or death if I get hit again.

She told me not to climb outside anymore. When I heard that, I was devastated. I thought about listening to my doctor, but I realized that if I stopped climbing outside, I would be like a fish without water. As an adult, I decided to climb outside, but I have to be very careful about where I climb; when I climb (not in the early spring when freeze-thaw is likely to cause rocks to fall); and I ALWAYS wear my helmet.

Sara, sporting her helmet!

I started climbing outside again at the end of March 2010; I went on the cross-country climbing road trip I had planned to embark on in July 2008, but because of my accident, it was postponed for two years. I took a huge risk, but I finally went. I lived the climber’s dream of living on the road in my van. I climbed at various climbing destinations across the country for the next nine months. But, before I climb with anyone new, I have to give a disclaimer.

I tell them about my accident and explain that because of my injury, I am at serious risk if I get hit again. I only use a Gri-Gri so that my partner is not at risk if something happens to me. If something does happen, all my brain scans are in a flash drive that lives in my pocket. Because I have to use a Gri-Gri, I can’t climb with doubles when I climb trad. I know that when I tell potential new climbing partners this, they might not want to climb with me.

But it is something I have to do now. There are friends of mine, who will not climb with me because they fear the risk, and I cannot get upset at them for that, unfortunately, it is just my reality now.

Because I was not wearing a helmet, I had a traumatic brain injury. I have had 12 surgeries between January of 2008 and November of 2011. Superficially I have a visible dent in my head. My skull is misaligned. I have a scar that goes from my forehead to the back of my head where hair will never grow. On a much deeper level my life has changed dramatically. I don’t have a lot of energy and I need a lot of sleep because if I am sleep deprived, chances of me having another seizure increase. I am on anti-seizure medication and will be for the rest of my life.

While I am on this drug, I cannot have children. The anti-seizure medication affects fetal brain growth, so if I do get pregnant, I put my child and myself at risk. Therefore, if I decide I want to have children, I will have to go off the medicine, and risk having another seizure. I have to work on ways to improve my memory every day. I graduated from Columbia University as an undergrad, yet I am too scared to go back to school for a graduate degree because I don’t trust my memory or my ability to stay in school.

Climbing in Apple Valley (CA) post accident

Safety First To Prevent Serious Climbing Accidents

I am sharing this story to reiterate how important climbing helmets are, and I hope that if one person reads this article and realizes the importance of helmets and becomes a helmet wearer, then at least something positive came out of my accident. The accident and the recovery were difficult and full of ups and downs. I thought that once I started climbing outside again, I would stop thinking about my accident, but I was wrong. I deal with the accident and its repercussions every day.

The perception of helmets is not just an individual climber’s problem; it’s an industry-wide problem. Sport climbers are never photographed with helmets. Petzl, Black Diamond, CAMP and Mammut all make terrific helmets, but the sponsored sport climbers never wear them. Why? Who has to die before the entire industry will promote helmet use for all climbers?

The climbing helmets that are being made these days are light and comfortable. My current helmet and my favorite so far is one of Petzl’s newest helmets, the Sirocco. The helmet is made out of car bumper material, is extremely lightweight, and is the most comfortable helmet I have ever worn! Some climbing guides prefer the Sirocco due to its longevity. Petzl has other helmets, including the Elia, the women’s specific suspension helmet that has a cutout for a ponytail. I just tried on a Black Diamond Vapor, another lightweight, well-ventilated comfortable helmet that I am thinking about purchasing; Mammut, and CAMP are other companies that make phenomenal helmets.

The right helmet for you is the one you will wear. If it is comfortable, you will wear it, so get the best helmet for you and protect your brain!

Happy Climbing and Climb Safe! ~Sara

After graduating from college Sara Gillers started climbing. She has lived on the road for 14 months climbing full time. Her passion for climbing is evident in everything she does. Whether it is coaching children on MetroRock’s climbing team or adults, or running the non-profit Urban Peaks, or just climbing. Climbing is truly her life. Even after an accident that almost killed her she is still happiest on the rock, whether it be sport or trad.